The "Boxer" and "Enterprise," Monhegan, 1831

This painting depicts an 1813 battle between the U.S. Brig Enterprise and the British Brig Boxer off of Monhegan Island. The separation movement stood at a standstill during the War of 1812, as allegiance to the United States took precedent over an independent Maine. Maine Historical Society

The War of 1812 proved a trying time for the separation movement in Maine. With the northern-most coastal territory in the Union, and a shared a border with British Canada, Mainers largely shifted their focus from separation to the war effort. After the war, however, the separation movement was revived.

In October 1815, the Portland-based Eastern Argus newspaper began a thirteen-article campaign promoting separation. Of its many arguments, the paper maintained a district with a population of nearly 270,000 deserved an independent government. With continuing public pressures, the General Court agreed to a hold a vote on the question in May, a month after the 1816 gubernatorial elections. However, the Court stipulated that the separationists must win by "a large majority" to be granted separation.[24]

Letter from Robert Boyd calling for a meeting in Gray to discuss Separation, 1816

Maine Historical Society

Although resulting in a nearly 4,000 vote victory for the separationists, another poor voter turnout provided Massachusetts little incentive to grant Maine its independence. While fewer than half of eligible voters cast a ballot, critical information became evident from the results when compared to the gubernatorial statistics from the previous month. For the first apparent time, the vote was split along party lines, with the Democratic-Republicans generally supporting separation and Federalists opposing. Additionally, the inland-coastal dichotomy still existed, with squatter-proprietor tensions and the Coasting Law likely still fueling the sentiments of the two voter bodies.[25]

Despite the vote's failure, separation was a widely debated topic on the floor of the General Court the following summer. The Federalist majority argued that because so many Maine citizens did not vote in May, the vote could not accurately depict the sentiment of the District. A joint committee concluded that a second vote would determine the fate of Maine independence. This vote, scheduled for September, would require a five-to-four majority for separation to pass. If it passed, a convention would be held in Brunswick later that month to draw up a new Maine constitution. If it did not, delegates would meet in Brunswick to develop a strategy to move forward.

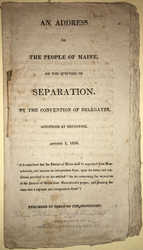

Anti-Separation Pamphlet, 1816The summer before the September 1816 vote, anti-separationists continued their opposition to an independent Maine. This pamphlet, which belonged to Stephen Longfellow IV, primarily discusses the financial burdens of separation.

To the dismay of the separationist movement, anti-separationists spent the summer organizing, and on Election Day in September they showed up by the thousands to cast their votes. Unable to achieve a five-fourths majority, Maine remained part of Massachusetts.[26] That fall, the infamous Brunswick Convention of 1816 stirred controversy over the voter tally, as the separationist delegation led by William Preble claimed an inaccuracy in the meaning of the term "majority." In response to Preble's faulty logic for a separationist victory, an angry Federalist remarked that "the motives of the majority are to be found in the deception of the human heart. The heart is deceitful above all things, and I may add, desperately wicked." By December, however, the General Court ended any further controversy, declaring it "inexpedient to adopt any further measures in regard to separation" and the movement would remain—for now—at a standstill.[27]

[24] Banks, Maine Becomes a State, 75.

[25] Banks, Maine Becomes a State, 82-87.

[26] Banks, Maine Becomes a State, 88-90, 108.

[27] Banks, Maine Becomes a State, 107-115.