The 1800s welcomed a plethora of economic and demographic changes for the District of Maine. The population had increased nearly fifty percent during the 1790s, and between 1794 and 1807 the shipping industry tripled. Perhaps most importantly, however, was the founding of 55 additional towns during the 1790s and another 53 in the first decade of the 19th century, as well as the incorporation of three new interior counties.[19] With this growth, the District evolved as it shed its infant skin and entered a stage of maturity—making it ripe for statehood.

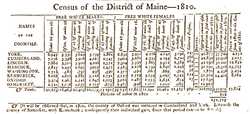

Census of the District of Maine, 1810Maine's population grew by 77,804 between 1800 and 1810. Published in the Eastern Argus, April 11, 1811 (vol. 8 no. 385)

The cover page of Ede's Kennebec Gazette, published in Augusta on January 6, 1803, illustrated why the separation movement had not yet succeeded. The full-page article outlined 24 points on why a separation was not only unnecessary, but also impractical. The anonymous author (perhaps Edes himself) wrote of a few different themes. The first and most important was the requirement of a strong military should a war break out. The state would be better defended as part of Massachusetts, the author argued. Further, Maine had more influence at the federal level if it remained a district of Massachusetts. The paper emphasized that “if any other attentions are required from Congress…they are more likely to be obtained upon the application of the seventeen delegates of Massachusetts and Maine united, than of the four delegates belonging to Maine alone.” The final primary argument was simply a lack of immediate motives. The author conceded that Mainers would be unhurt should they separate, but argued it was not necessary at the moment.[20]

William King, Bath, ca. 1806

William King became a prominent figure in 19th century Maine separation politics and would continue to play a major role in early statehood as Mane's first governor. Patten Free Library

The separationists and anti-separationists heard and acknowledged the other side's arguments. At a time of national crisis with Britain, it was a burden to the national government and potentially hazardous to attempt a separation. But in the opinion of many, separation was potentially in the best economic interest for Maine. By 1807, the idea of separation was again emerging with force. This time, however, it came from the top down. Convincing statesmanship—undoubtedly stirred up by crafty government officials from Maine such as William King and William Widgery—got the question of separation before the General Court. On February 9, 1807, the upcoming Massachusetts gubernatorial elections were also declared a day to vote on Maine's separation.[21] With more than half the voting population casting a ballot, the 1807 vote involved by far the largest number of citizens considering the question of separation to date.[22] Yet the result proved unfruitful for separationists as the vote was an overwhelming defeat, 9,404 against to 3,370 in favor.[23]

[19] Banks, Maine Becomes a State, 41.

[20] Edes’ Kennebec Gazette, 1/6/1803.

[21] Banks, Maine Becomes a State, 52.

[22] Banks, Maine Becomes a State, 45. The votes displayed by Banks show 12,774 votes casted considering separation compared to the 20,424 who voted for governor.

[23] Banks, Maine Becomes a State, 53.